Digitalisation

Digital transition with open government at heart

This article explores how open government and digital transition relate to each other and identifies the challenges of the digital transformation of public-sector services. It first looks at what open government means in practice and examines its three pillars – transparency, civic participation and collaboration in delivery of public services. It then explores how information and communication technology has redefined the open government concept and discusses principles of open government data. Lastly, it looks at open government today, amid rising civic expectations in democratic systems, waning trust in governments and increased digitisation of public services due to the Covid-19 pandemic, with an example of a digital transformation project taking open government ideas to new levels.

Introduction

The concept of open government emerged in a post-World War II context, where transparency about decision-making on public matters and disclosure of information by governments were seen as extremely important. The key messages of open government are establishing transparent and collaborative governance systems in the public sector that differ from market-oriented commercial relationships or bureaucratic principles1 of traditional hierarchical governments and bridging the gap between the governing and the governed.

The expansion of information and communication technologies redefined the open government idea. Today, open government focuses on how to better navigate the challenges of the digital economy and the increasingly digitalised collective public life of communities and nations. The digital transformation of the public sector with open government at the core changes the way governments interact with society, the way information is disclosed and how people engage in public affairs.

US President Barack Obama steered efforts to embed open government in digital transformation policies and issued a memorandum on public data to ensure that the US government was transparent.2 Today, notions of open government are likely to be more visible and respected by citizens in countries emerging from autocracies and dictatorships and adopting democratic rule. Unsurprisingly, open government thinking is a cornerstone of public-sector digital transformation policies in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Portugal. In Europe, open government remains at the heart of the European Union’s (EU) digital agenda, but has only gradually found its way into the regulatory frameworks of former Soviet bloc countries.

The authors would like to thank Paloma Croset Suarez, Consultant, EBRD, for her research and assistance in the drafting of this article.

Today, open government focuses on how to better navigate the challenges of the digital economy and the increasingly digitalised collective public life of communities and nations.

When governments are open

Open government is a public-sector governance strategy that aims to establish structures at all levels of government that build on information transparency to citizens and their engagement in public decision-making to encourage participative and collaborative governance systems in the public sector. For example, a main proposition of the US open government directive is “to establish a transparent governing structure allowing empowered citizens to participate”.3 Key policy instruments, such as the US Memorandum on Transparency and Open Government and the US Open Government Directive, conceptualise it as “a new governing structure, highlighting proactive information dissemination (transparency) and accessible participatory mediums for decision-making or public service provision (participation/collaboration)”.4

A government is considered open – that is, it works based on open government principles – when information transparency, civic participation and collaboration mechanisms guide regulatory frameworks and legislative processes for all public matters, from government relationships with citizens and business to regulation of the delivery of public services.

A government is considered open when information transparency, civic participation and collaboration mechanisms guide regulatory frameworks and legislative processes for all public matters.

Three pillars of open government

Transparency

Government transparency is a way to create openness by disclosing information about government actions and processes. Transparency increases individuals’ trust in government and enhances the legitimacy of government, as citizens are aware of the decisions it adopts. Transparency is a new model of government, with information transparency policies5 on all public matters. This means unrestricted access to information, accountability and open data.6 The conditions for accessing data, as well as documents about the actions and decision-making processes of public officials, define the rights and obligations of individuals.7

Transparency policies have developed rapidly with the rise of new technologies. Transparency implies that government data are published online, as there is a critical difference between a mere ex-post disclosure of information and online publication of information that actually promotes transparency of governance processes by enabling citizens to act in due time.8 It is therefore important to have laws that clearly define the context and type of information that must be disclosed online and when. While transparency is a condition for fulfilling the other criteria of participation and collaboration, it is not in itself sufficient to achieve the goal of open government in public-sector governance.

Participation

Citizens (and organisations from the private sector and civil society) use social collective actions to influence government decision-making. These are not linked to a general election and other political mechanisms, but aim to provide feedback on public policy and government decisions. Still, even democracies struggle to invent effective means for citizen and civic participation in government decision-making, and this is where technology can play a big role.

Modern technologies enable diverse ways to interact and, in particular, establish working relationships between citizens and government officials, not limited to direct political participation. This is a challenge for governments – the need to develop policies and e-government tools creating new interaction channels, allowing citizens’ voices to be heard on government decision-making. Another challenge is related to providing regulatory and operational frameworks for collaboration with the government in delivery of public interest services.

Collaboration

Collaboration with government on public service delivery is associated with the concepts of interoperability, co-production and civic tech innovation. Civic activists would like to influence the design, provision and evaluation of public services, in particular when governments start to deliver public services in a digital format, to achieve a better fit with the needs of their local communities. Collaboration of citizens and business communities with government bodies on the delivery of public services remains unexplored territory. This is mainly because an idea of civic co-production with government departments requires different protocols of engagement compared to traditional in-house public service delivery or public procurement contract-based sourcing from the market. As regulatory frameworks for operational interaction between public bodies and civil society organisations and pro-bono business communities are very new and untested, they are a novel regulatory concept for many governments.

In terms of regulatory challenges, it is easiest to introduce transparency requirements for government decisions. Several governments in the world excel in ex-post transparency communications and call themselves very transparent. It is more difficult to design and regulate a non-political transparency procedure that works ex-ante and enables civic and business participation in the process before decisions are made. Still more difficult is setting up rules for collaboration with civic activists or not-for-profit organisations seeking to contribute to the delivery of specific public services to their local communities. This is particularly difficult when these civic organisations do not fall into any of the well-established legal definitions of (a) a charity, (b) public procurement supplier or contractor or (c) political lobbyist. And the challenge increases when civic collaboration is proposed on sensitive (and expensive for the taxpayer) public services, such as education and healthcare.

When government data are open

While regulation of open government strategies involves much more, it is true that at the bottom of all transparency, participation or collaboration mechanisms in the public sector, there is a question of access and re-use of government-created and held information. In other words, there is no open government without open government data, and this is where part of the difficulty begins.

First, there is no legal definition of open government data – data created and administered by public entities – as a common good in the directly binding international legal instruments. Open government data are still defined by an original industry standard of 2007: complete, primary, timely, accessible, machine-processable, non-discriminatory, non-proprietary and licence-free.9 The closest substitute is a G8 Open Data Charter signed in 2013 that outlines five principles of open government data: open data by default, quality and quantity, useable by all, releasing data for improved governance and releasing data for innovation.10

Second, legal openness of government information means different things in different countries. The less democratic rule, the less government-generated information falls into the category of government open data. The latest EU policy on the concept describes open data as information that is obtainable by everyone, machine-readable, offered online at zero cost and has no restrictions on re-use and distribution. Readiness to open and share government data is a next step, as a regulatory framework for governing the re-use by third parties of datasets produced by public institutions is an important political tool to encourage democratic citizens’ participation in public affairs.11 Aiming to improve transparency, citizen involvement and cooperation, as well as social and economic value, data created and administered by public entities shall be both legally and technically available for use electronically.12 Therefore, it is the technical/technological capacity of the government to effectively open and share data for re-use that shifts public-sector open government strategies from “legally enabling access” to “facilitating active participation” of citizens in public matters.

Third, data created and administered by public entities are what governments use to make governance decisions about citizens and businesses.13 One of the reasons citizens expect this information to be published as open government data is to ensure that these data equally benefit all entities dealing with the government, namely citizens, businesses and government itself.14 As such, government open data are at the core of e-government – that is, “the use of information technologies to deliver to all citizens government services, information and knowledge to facilitate greater access to the governing process and deeper citizen participation”.15

While all understand that data access and data sharing are key to effective governance and the running of public services, citizens (as well as businesses) are sceptical of government data use. Levels of trust vary, but at the bottom of this distrust is the fact that development of e-government services has not been accompanied by a proportionate increase in transparency of government data. Although e-government originated in open government concepts, government technology policies and strategies were often developed to serve primarily government departments, not citizens’ needs. As such, there was no care about government open data quality and no appreciation of the value of government open data and its sharing for the benefit of all stakeholders, including the government as a whole. Historically, this was partly due to inadequacies and prohibitive costs of technology and perceived risks in data sharing.

To gain citizens’ trust, governments proclaimed high standards of security of government-handled data and promoted policies restricting access to government data. Development of protocols for secure government data opening and sharing was perceived as a risk. Lack of regulatory standards for opening data created and/or administered by the government also played a role. Today, progress in technology has brought forward several methodological and policy concepts for data interoperability, automated online data collection and online publication of data generated in the e-government systems. However, there are still no well-established regulatory standards for real-time government data extraction from e-government systems and their online publication for opening and sharing in the machine-readable format. Without exploring new models of citizen legal consent, citizen and government data ownership, designing enabling regulatory frameworks for effective primary and secondary use of data is not possible. And without new rules of operation that both citizens and business can trust, there are few opportunities of interaction between public bodies and civil society in relation to the provision of public services, particularly public services using government open data.

Modern technologies enable diverse ways to interact and, in particular, establish working relationships between citizens and government officials, not limited to direct political participation.

New regulatory standard of the European Union

Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and the European Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public-sector information aims to bring open government laws in line with advances in digital technologies. By default, the re-use of documents shall be free of charge and an open data regime enforced via an obligation of public-sector bodies and some public enterprises to make public data available as open data, not only upon request. Open data shall also be data in an open format that can be used freely, re-used and shared by anyone for any purpose.16

Public-sector bodies shall make dynamic data available for re-use immediately after collection, via suitable application programming interfaces (APIs) and, where relevant, as a bulk download.17 Dynamic data means digital documents, subject to frequent or real-time updates, in particular, because of their volatility or rapid obsolescence.18 Also, high-value datasets shall be made available for re-use in a machine-readable format, via suitable APIs and, where relevant, as a bulk download.19 High-value datasets support society, the environment and the economy by contributing to the creation of value-added services, applications and new, high-quality and decent jobs that can benefit many people.20 In relation to exclusive arrangements, the re-use of documents shall be open to all potential actors in the market, even if one or more market actors already exploit value-added products based on contracts or other arrangements between public-sector bodies or public undertakings.

Tackling legal barriers

In spite of policy development, governments still face challenges due to the lack of international legal standards for:

Government-to-business data sharing – The public sector makes more of the data it generates available for use as open data, especially by small and medium-sized enterprises that use it to develop new data-driven commercial and public services.

Business-to-government data sharing – Not enough private-sector data are available for re-use by the public sector to improve evidence-driven policymaking and public services, and there are too few tools in the public sector to make use of available data without a need for duplicated data collection for public governance purposes. Legal frameworks are needed that offer appropriate incentives to create a data-sharing culture and encourage the re-use of private-sector data for the public interest.

Sharing of data between public authorities – This can make a remarkable contribution to improving policymaking and public services, but also to reduce the administrative burden on companies by implementing “single window” digital public services and the “once only” principle.

Insufficient regulatory frameworks therefore prevent citizen-sourcing as well as more modern and collaborative ways of business-sourcing that aim to promote innovation in public services.

Citizen-sourcing is participatory- and innovation-oriented. This public-sector governance mechanism enables public organisations, as sectoral regulatory authorities, to engage with citizens via online intermediary platforms and seek innovative ideas and solutions that are better suited for the digital economy than services traditionally performed by public servants or outsourced to commercial operators. In addition to quick wins – such as greater trust in government decisions – these mechanisms encourage public service innovation and cutting programming costs for sectoral initiatives as new ideas are collected and new services piloted with civic activists. These policies focus on “citizen co-production” and are based on the development of new online digital tools for public services – transformative “civic tech for govtech”. They promote innovation, enhance democratic participation, invite wide public involvement in policy implementation and improve law enforcement.

Using a new digital platform to disseminate government information and policies is not a condition for the success of citizen-sourcing. Rather, it happens when informed citizens can use an online digital platform to participate in and contribute to public service delivery, because only citizen co-production enhances public-sector accountability. Without co-production, there is an illusion of government openness without a truly open government to improve public services delivery.

Creating a regulatory framework for citizen- and business-sourcing in public healthcare services: EBRD pilot collaboration with the Slovak Republic

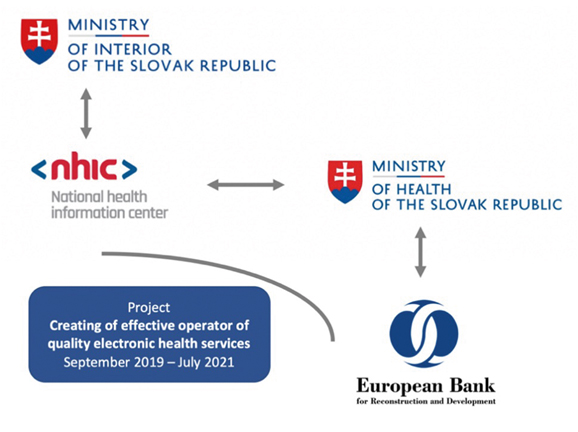

Enabling open government citizen- and business-sourcing is challenging for any public-sector service, but perhaps none is more sensitive than public healthcare. The Slovak Republic aims to create a new type of public body – a national agency operating digital healthcare services (eHealth) for the Ministry of Health. The reform programme focuses on digital transformation of the National Health Information Centre (NHIC), operator of the eHealth system, and introduces data-driven analytics to centralise public procurement in the country’s national healthcare system. The objective is to transform the NHIC into a modern public-sector organisation providing proactive digital services to healthcare sector stakeholders, including mobile health (mHealth) services. Similarly, public procurement improvements aim to better control procurement processes of medical supply and devices.

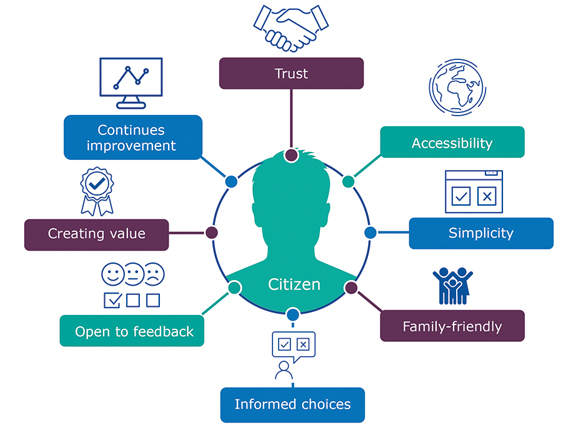

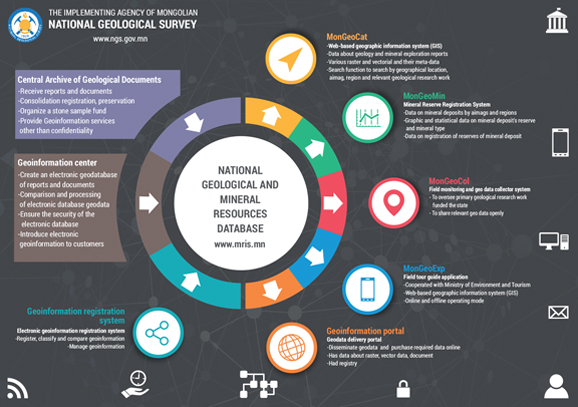

Source: EBRD

As Figure 1 shows, the EBRD teamed up with the Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic in 2019 for a pilot project, bringing in international expertise and peer organisations to introduce the latest concepts from global digitalisation leaders for healthcare procurement and digital healthcare services. The EBRD helped to identify open government policies for public healthcare and highlight key values and principles for citizen-centred design of public healthcare services (see Figure 2).

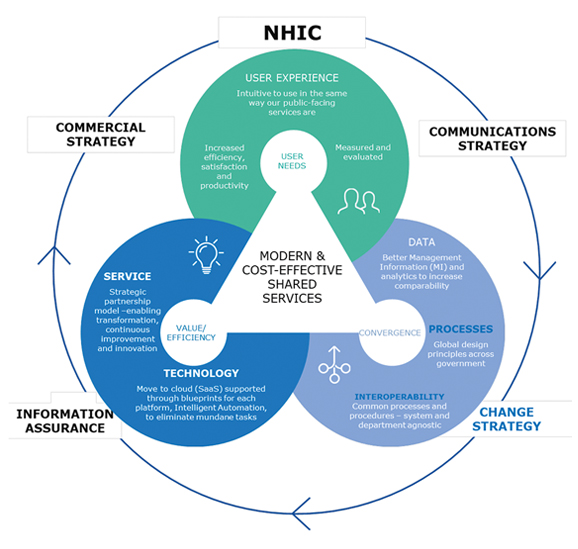

Source: EBRD

Policy workshops with peer organisations from Portugal facilitated verification of policy concepts in the context of the EU acquis and specified business models and regulatory approaches to develop the vision of digital eHealth and mHealth services. Key business concepts were formulated for the NHIC as a provider of information technology (IT) shared services for public healthcare. In particular, two areas were found to be critical for NHIC’s mission. One was a policy framework for open data and digital data-driven e-services, to lead digital transformation of public healthcare services. The second was a digital public procurement data to enable the creation of a modern, centralised medical purchasing agency for the Ministry of Health and to introduce better cost control and more efficient, data-driven medical supply chain management. Questions remain about the licencing terms for secondary use of health and healthcare data, as there are models of open data licences and no identifiable global best practice for secondary use of health and healthcare data.

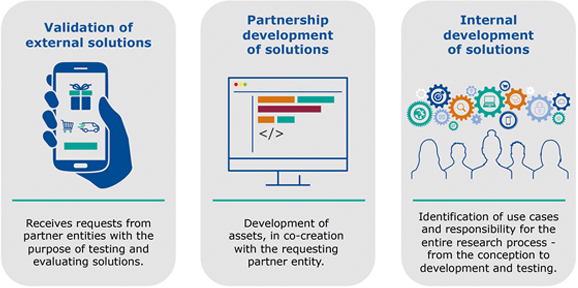

Source: EBRD

Note: The National Health Information Centre is called Národné centrum zdravotníckych informácií in Slovakian.

- NHIC IT Shared Services and mHealth ensure equal access to most advanced treatments in public healthcare, with no digital divide, improved quality and without making it more expensive for citizens and state budget

- NHIC governs primary and secondary use data holistically throughout its lifecycle to ensure regulatory compliance and security and promote data access and usage by all healthcare stakeholders

- NHIC excels in providing modern customer-oriented electronic products and services and is recognised for quality of ‘single window’ smart communication towards all healthcare stakeholders

- NHIC helps creating data-literate healthcare civil servants through new world-class training at Data Academy and the Medical Data Science Partnerships with peer organisations in Europe

- Public procurement will be soon procure-to-pay digital and NHIC healthcare procurement data is all-digital-ready and supporting centralised medical purchasing

To deliver innovation and new business concepts, new policies and regulatory frameworks are needed to support and regulate eHealth and mHealth services, in particular:

- Secure access and health data sharing: Citizen access to personal health data at both national and EU levels.

- Cross-border access to anonymised data for research and personalised medicine (secondary use of data): Promotion of a European data infrastructure to support information sharing among healthcare professionals in the EU.

- Empowering citizens to use digital healthcare instruments to their advantage: Teach people how to use digital instruments proactively to care for their health, nurture prevention and interact with healthcare providers.

Following identification of the most innovative practices for regulation of primary and secondary use of data (in addition to Portugal, the latest policy developments in Chile, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands and the United States were reviewed), a proposal was designed for a regulatory framework to answer important legal questions about governance models for citizen- and business-sourcing. It covers secondary use of healthcare data and data on medical public procurement to create models for collaboration with civic tech organisations, academic research centres and business start-ups on eHealth and mHealth digital services. To reach the market quickly, a new regulatory process for three parallel streams is proposed: (a) validation of external solutions developed by the market, (b) mHealth applications and devices created jointly by public and private entities and (c) internal development, involving data sharing between different government entities.

Model of a regulatory framework for open data and secondary use of healthcare data

To promote new eHealth and mHealth digital services to citizens and medical professionals, NHIC needs a new regulation to change the way patients’ health data, other healthcare data and medical public procurement data are handled. This is a major change, as it involves citizens’ legal consent regarding sensitive health data, government-to-business data sharing, sharing of data between public authorities and public healthcare organisations, and business-to-government data sharing between healthcare regulators and commercial healthcare insurers in the Slovak Republic. New rules must specify the conditions for re-use or secondary use of health data and data on medical public procurement and recommend formats for open data sharing, rules to charge for health and healthcare datasets, and standard terms of use and licences for eHealth and mHealth services.

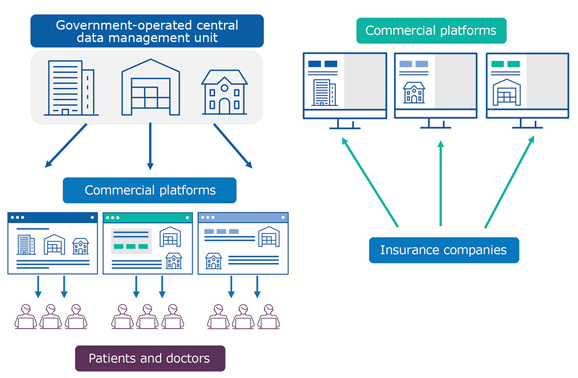

Regulatory change is also needed to enable NHIC to introduce new business processes (see Figure 4) for collaborative development and delivery of new eHealth and mHealth services (see Figure 5). mHealth applications for smartphones exist and show promising results but are not in clinical use due to the missing regulation. In particular, creating partnerships in prototyping and developing new IT solutions and devices for mHealth services (identified as potentially the most cost-effective approach to mHealth) and shared delivery of mHealth services by NHIC in collaboration with commercial IT vendors go beyond contracting options available in current public procurement and concession laws and existing regulation of government IT shared services in the Slovak Republic.

Source: EBRD

Source: EBRD

INNOVATIVE 2-TIER ARCHITECTURE

A government-operated mHealth central data management platform is connected to commercial platforms through a secure API, based on regulation and/or contract with NHIC

Commercial platforms interact with citizens, healthcare providers and insurers to provide them with basic (free of charge) or extra-charge mHealth services, based on a contract with insurers

OPEN DATA

Open data is deposited in a public central data management platform and is real-time open and accessible to everyone

Restricted data is controlled by data owners

Any commercial provider can develop its own platform/services based on open data

Without co-production, there is an illusion of government openness without a truly open government to improve public services delivery.

The NHIC eHealth system shall further automate data collection by government, commercial entities and patients. New data governance processes shall separate health data and healthcare data into restricted, closed and open datasets that are published online in relevant repositories and available for appropriate re-use. Data governance mechanisms and the anonymisation of data for secondary use must lead to data that are available online, machine-readable, accessible, findable and re-usable together with their metadata and, where possible, in open data formats of JavaScript Object Notation formats, which are popular with the IT industry. Datasets qualified for secondary use shall be made available for open re-use in machine-readable format, via suitable APIs and/or as bulk download.

To avoid creating barriers in data re-use that may limit development of new mHealth digital services, NHIC should consider making secondary data available for free or exceptionally charged at the marginal cost of dissemination, when NHIC needs to generate revenue to cover part of the costs of data collection and governance. In addition to defining certification procedures for mHealth services and devices, to make mHealth services sustainable, the Ministry of Health must decide and adopt user-pay tariffs/charges for mHealth services and specify any applicable conditions for including mHealth services and devices in doctors’ prescriptions and reimbursing the cost of eHealth and mHealth services from public health insurance. Based on this, NHIC would be able to develop online charging systems for eHealth and mHealth services, both available by medical prescription and refundable from public health insurance as well as certified but non-refundable and only for private purchase.

The institutional transformation of NHIC progresses. However, challenges the Ministry of Health faces in managing healthcare during the Covid-19 pandemic have delayed legislative initiatives and implementation of the new regulatory concepts in practice. If implemented, the Slovak Republic would introduce a very advanced open government regulatory and business concept for secondary use of healthcare and medical procurement data and sustainable “mHealth on prescription” models for mHealth applications/devices in Europe’s public healthcare system.

H.R. Adnan, A.N. Hidayanto, B. Purwandari, M. Kosandi, W.R. Fitriani and S. Kurnia (2019), Multi-Dimensional Perspective on Factors Influencing Technology Adoption for Open Government Initiatives: A Systematic Literature Review, International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and information Systems, pp. 369-374.

M.I. Ali Hassan and H. Twinomurinzi (2018), “A Systematic Literature Review of Open Government Data Research: Challenges, Opportunities and Gaps,” 2018 Open Innovations Conference, pp. 299-304, doi: 10.1109/OI.2018.8535794.

J. Bates (2014), “The strategic importance of information policy for the contemporary neoliberal state: The case of Open Government Data in the United Kingdom,” in Government Information Quarterly, 31 (3), pp. 388-395.

I.C. Dorobăț and V. Posea (2021), “Open Data Indicator: An Accumulative Methodology for Measuring the Quality of Open Government Data,” 13th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence, pp. 1-4, doi: 10.1109/ECAI52376.2021.9515147.

European Union (2019), Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 in Official Journal of the European Union. See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L1024&from=EN

P.T. Jaeger and J.C. Bertot (2010), “Transparency and technological change: Ensuring equal and sustained public access to government information,” in Government Information Quarterly, 27, pp. 371-376.

T. Kuang-Ting (2021), “Open government research over a decade: A systematic review,” in Government Information Quarterly, 38, p. 101566.

M. Osorio-Sanabria, J. Brito-Carvajal, H. Astudillo, F. Amaya-Fernández and M. González-Zabala (2020), “Evaluating Open Government Data Programs: A Systematic Mapping Study,” Seventh International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, pp. 157-164. 10.1109/ICEDEG48599.2020.9096755.

E.A. Ruvalcaba-Gómez and C. Renteria (2020), “Contrasting perceptions about transparency, citizen participation, and open government between civil society organization and government,” in Information Polity, 25, pp. 323-337.

V. Wang and D. Shepherd (2020), “Exploring the extent of openness of open government data – A critique of open government datasets in the UK,” in Government Information Quarterly, 37, p. 101405.

To promote new eHealth and mHealth digital services to citizens and medical professionals, The National Health Information Centre needs a new regulation to change the way patients’ health data, other healthcare data and medical public procurement data are handled.

Accelerating the Polish digital transformation agenda by facilitating the use of cloud and blockchain in the public sector

The isolation and social-distancing rules imposed to tackle the Covid-19 pandemic have brought about many (temporary and permanent) changes in the way we lead our lives. While everyone is scrambling and catching up to the new reality, one thing is clear: the “new normal” is more digital. And going digital in today’s world is not just a precondition to thrive and succeed – it is more fundamental than that. It is a precondition to survive and remain relevant.

The recent economic crunch, coupled with inflation and the ever-increasing cost of living, have forced the hands of many governments to intervene and provide financial subsidies to alleviate the negative impact on citizens’ lives. Such unanticipated costs have pushed governments to rethink and re-jig their public spending priorities and accentuated the need for more efficient, digital and transparent delivery of public services.

While this new reality has compelled many governments to prioritise the design and delivery of digital transformation strategies, some countries were working on their digital transformation strategies well before the crisis. Such is the case of Poland.

With a dedicated ministry dealing with digitalisation between 2011-21, the digital angle has been at the forefront of the Polish state strategic vision for a long time. Among the many strategic documents, Digital Poland for 2014-2020 identified “effective and user-friendly public e-services” as a key area of focus.21 Yet, despite its long-time focus, work and efforts on digitalisation, Poland has continued to lag behind its European Union (EU) peers. The Digital Economy and Society Index 2018 ranked Poland as 24th of 28 EU member states in the field of the digitisation of the economy.22 23

EBRD’s work with the Chancellery of the Prime Minister of Poland

To achieve greater digitisation of government services, Poland’s Ministry of Digital Affairs24 approached the EBRD in 2018 with a request for assistance to:

- increase the uptake of cloud computing across government administrations and local public authorities throughout Poland (Cloud Workstream) and

- explore the possible uses of the distributed ledger technology (DLT) in the Polish public sector (DLT Workstream).

With funding from the European Commission’s Structural Reform Support Programme in 2019-21, the EBRD’s Legal Transition Team – with the assistance of external consultants from Ashurst, R3 and Maruta Wachta – successfully delivered on this request.

Going digital in today’s world is not just a precondition to thrive and succeed – it is more fundamental than that. It is a precondition to survive and remain relevant.

The Cloud workstream

Since the early 2010s, governments around the world have introduced so-called cloud-first policies to prioritise the acquisition (where appropriate) of cloud-based information technology (IT) solutions by public-sector organisations. In practical terms, this means that public-sector organisations should consider and fully evaluate cloud solutions when procuring IT services before considering any other option. The ultimate aim of this policy is to ensure that the IT infrastructure retained offers the best value for money.

In the United Kingdom, for example, IT procurement is effected through the digital marketplace – a portal for ordering services, including cloud services – with cloud services purchased under prescribed framework agreements with pre-approved service providers within the so-called G-Cloud model.

This G-Cloud model was a reference point for the Polish Common State IT Infrastructure Program (WIIP), adopted through a resolution by the Council of Ministers of Poland on 24 September 2019. The WIIP promotes Poland’s own cloud-first policy and recognises the benefits that cloud solutions offer when developing new IT solutions in public administration.

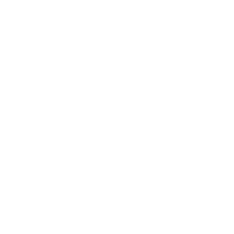

Cloud computing at a glance

The National Institute of Standards and Technology defines cloud computing as a model to enable ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (for example, networks, servers, storage, applications and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction. In other words, cloud computing is a method of storing, retrieving and processing data, and accessing software programmes, over the internet (or other networks). Instead of buying, owning and maintaining the physical assets (such as servers) at on-premises data centres, one can access technology services, including computing power, storage, network, security services and software applications, on an as-needed basis from the relevant cloud provider. This can enable faster innovation, flexible resourcing and considerable economies of scale.

Source: EBRD, Ashurst, Maruta Wachta and R3 (2021)

With respect to the cloud component of the technical assistance request, the Chancellery of the Prime Minister was mainly interested in:

- raising awareness among the public authority bodies in Poland about the benefits of cloud solutions (in relation to the “on-site” alternatives) and

- guiding the public authorities in Poland on how to procure cloud-based IT solutions.

To this end, we produced the cloud guidelines aimed at government administration and local public authorities in Poland.25 This guide, part of the WIIP, is supposed to help government administration and local public authorities in Poland determine the potential application of cloud computing solutions as part of their decision-making process when procuring new, or refreshing existing, IT resources. To this end, the guide explains what cloud computing offers and the benefits of adopting a cloud-based solution, and sets a framework to help evaluate what data are suitable for the cloud. The use of the cloud also raises important considerations around security, privacy and resilience and the guide outlines these key considerations in separate, specific sections.

In addition, to help government officials negotiate service levels with cloud service providers, we prepared template service level agreements, accompanied with annotations to indicate the rationale and importance of the key provisions typically found in such agreements.

IT infrastructure is essential for the functioning of every public administration body. When the infrastructure becomes outdated, new resources must be procured. Nowadays, IT infrastructure can be hosted on-premises or on the cloud, and deciding between these two options depends on many variables. However, due to its numerous advantages (see Figure 1 above), there should be a clear preference to go for the cloud alternative, when possible. A simple example is data storage. Instead of stocking physical server machines, which have high initial costs and maintenance costs and take up a huge amount of space, public administration bodies in Poland can procure the services of a cloud service provider and have all their data stored in this provider’s data centres.

Cloud computing is a method of storing, retrieving and processing data, and accessing software programmes, over the internet (or other networks).

THE DISTRIBUTED LEDGER TECHNOLOGY WORKSTREAM

A subset of distributed ledger technologies, blockchain enables the creation of records of shared facts secured using cryptography to create an audit trail that is maintained and validated by those using the network (without requiring a third-party intermediary). These data are cryptographically assured and can be synchronised and distributed across multiple institutions. This enables anyone with access to the network to view the same information as other network users and creates the capacity to record shared facts across independent participants.

As the Covid-19 crisis has demonstrated worldwide, governments cannot rely on the old ways of administering to meet the challenges of the present or future. Identifying which services could be led or supplemented by digital solutions must become a major driver of public-sector reform.

As part of this technical assistance project with the Chancellery of the Prime Minister, we drafted a study to improve awareness among government stakeholders on the types, benefits and potential of blockchain in fostering transparency of government services. Drafted in conjunction with colleagues at the Chancellery of the Prime Minister, the study outlines the fundamental technical elements of the technology in a simple way, so it can be understood by a lay audience. To encourage its use, the study highlights the current landscape with regard to public- and private-sector use-cases to illustrate where the technology is being applied and where it would be well-suited to public-sector deployment in the future. Furthermore, the study outlines the legal considerations of blockchain solutions. It concludes that there are no clear minimum requirements to implement blockchain and/or specific provisions of Polish law that would explicitly exclude the possibility of using blockchain for governmental purposes. However, any legal framework under which blockchain can be successfully deployed should provide a level of clarity around three key but complex topics: (1) the legal status of crypto-assets, (2) the legal status of smart contracts and (3) compatibility with the existing regulation (such as data privacy, digital identification and authentication).

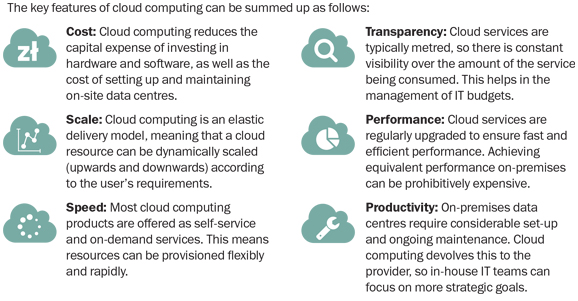

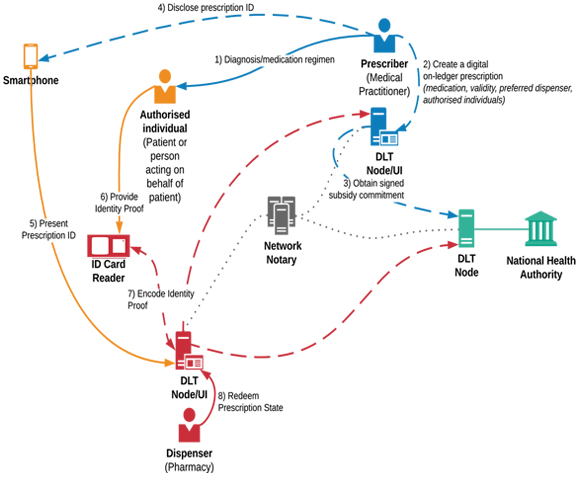

To illustrate the potential of the technology, the study outlines and discusses three use-cases: one in the financial sector, one in healthcare and the other in education. In each case, a high-level technical architecture and a walk-through of operations is provided along with guidance on how such solutions could operate in Poland. These use-cases are designed to emphasise the flexibility of the technology and its capacity to work within existing frameworks, making blockchain solutions an attractive prospect.

Source: study by EBRD in cooperation with R3/Ashurst/Maruta)

Benefits:

- Capacity to verify collection of prescriptions by patient (or known substitute)

- Traceability in the prescription services from prescriber to distributer and then to patient

- Capacity for prescriber to correct prescription errors

- Efficiency and reduction of time lost to error correction

- Peace of mind for patient in knowing that the prescription is correct

- Creation of digital audit trail for authorities in tracking and monitoring prescription services and potential for the created data set to inform future policy decisions. Such data could include geographic activity, type, origin and manufacture of medicines dispensed

Source: study by EBRD in cooperation with R3/Ashurst/Maruta)

Benefits:

- Streamlining of application processes for candidate and employer

- Reduction of fraud through the verifiable proof of original qualification

- Capacity for awards to be more effectively revoked

- Capacity for awarding institutions to have status revoked

- Could lead and inspire the development of increased use of digital solutions in identity

The study was presented in January 2021 to a wide audience including local and international representatives from the public and private sectors.

In the e-prescriptions case study (see Figure 2) the use of blockchain would add traceability to the prescription chain. Every party (the general practitioner, the patient and the pharmacist) would have a view of the situation at all times. This blockchain-enabled, digital audit trail would also help national health authorities to track and monitor prescription services to inform future policy decisions.

In the education case study (see Figure 3), credentials (that is, certifications) stored on a blockchain database, would create a more trustworthy system where the reliant party (that is, an employer) would have full certainty that the certification presented by a certain candidate is genuine.

We drafted a study to improve awareness among government stakeholders on the types, benefits and potential of blockchain in fostering transparency of government services.

Governments cannot rely on the old ways of administering to meet the challenges of the present or future. Identifying which services could be led or supplemented by digital solutions must become a major driver of public-sector reform.

Conclusion: Driving development with technology

The limitations in the day-to-day interactions brought about by the pandemic, including mandatory isolation and social-distancing rules, have spurred many governments around the world to think about introducing or revamping their digital transformation agendas. It is clear that the “new normal” will be far more tech-driven and, as such, will present new challenges. Both cloud-based solutions and blockchain have important roles to play in this digital transformation, but deploying real-life use-cases based on such technologies triggers important legal, technical and operational considerations that need careful assessment to ensure a smooth transition with lasting benefits.

The EBRD is here to lend a helping hand to overcome such challenges. Digital transition is at the heart of the EBRD’s mandate and is one of the three key strategic themes in our 2021-2025 Strategic Capital Framework. The central aim of this strategic theme is to unleash the power of technology to bring about change for the better in our economies of operation. And when it comes to realising this strategic ambition, in addition to actual investments, we will also engage in policy dialogue, capacity building and advisory activities, develop knowledge products and create strategic partnerships.

The central aim of this strategic theme is to unleash the power of technology to bring about change for the better in our economies of operation.

How can eProcurement serve public-private partnership projects, including concessions?

Executive summary

This article examines the feasibility of using electronic public procurement (eProcurement) tools to select a private party in public-private partnership (PPP) projects, including concessions. For the purpose of this article, PPP projects are discussed together with concessions (PPP projects/concessions). The challenges for governments mainly relate to (a) the relevance of international standards on procurement for PPP/concession procurement, (b) identifying international standards for eProcurement applicable to PPP/concession projects and (c) applying international (and regional) standards on electronic commerce (electronic signatures, platforms and emerging technologies in and for trade, such as artificial intelligence, Internet of Things, big data analytics and distributed ledger technology) to PPP/concession projects.

Practical experience with eProcurement tools for PPPs, including concessions, is limited. As a result, few operational details are known about using eProcurement to select private parties in practice. Public procurement policy, concession governance and public-sector digitalisation standards, including the use of platforms, functional equivalence, technology neutrality or smart contracts, need to be revisited to explore the opportunities for eProcurement in PPP/concession projects. For this reason, the Bank collaborates with the Sustainable Infrastructure Foundation, its SOURCE platform and interested governments in the EBRD regions to define a recipe for eProcurement for PPP/concession projects and inspire governments designing their PPP programmes to invest in digital governance tools for their PPP/concession projects.

Characteristics of PPP transactions that affect the procurement process

PPPs/concessions play a key role in government programmes designed to promote private-sector investment in infrastructure and delivery of public services. PPPs/concessions permit the mobilisation of private capital, expertise and know-how to complement state budgets and other public resources and attract direct private investment in public infrastructure and public services.

The United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Legislative Provisions on Public-Private Partnerships defines PPP (Art. 2.a) as an agreement between a contracting authority and a private entity for the implementation of a project, against payments by the contracting authority or the users of the facility, including both those projects that entail a transfer of the demand risk to the private partner (“concession PPPs”) and those other types of PPPs that do not entail such risk transfer (“non-concession PPPs”). At the same time, the 2011 UNCITRAL Model Law on Public Procurement defines procurement as the acquisition of goods, construction or services by a procuring entity, and a procurement contract as a contract concluded between the procuring entity and a supplier (or suppliers) or a contractor (or contractors) at the end of the procurement proceedings.

Therefore, the main features of PPP/concession projects that distinguish them from regular public procurement contracts to purchase goods, services or works are their complexity; focus on delivery of workable public infrastructure or public services over a long-term contract; development (or significant upgrade or renovation) and management of a public asset (including potentially the management of a related public service) as well as the structure of the transaction. Furthermore, the private party bears substantial management responsibility and risks through the life of the contract and typically provides finance, which is at risk. Remuneration by definition is largely linked to performance and/or the demand for or use of the asset or service.

The question remains how this contractual complexity, performance-based remuneration and longevity of PPP/concession public contracts affect the procurement process, which otherwise has all the features of standard procurement.

First, the pre-selection criteria must identify and describe the necessary professional, technical and environmental qualifications, professional and technical competence, personnel, experience and managerial capability to carry out all phases of the project. Second, the period to submit, prepare and revise proposals should be commensurate with the complexity of the project. Third, subsequent variations in the specifications or other requirements of the project cannot be excluded. Finally, awarding procedures must be appropriate. Unlike small-scale projects, complex infrastructure projects may require the use of consultation or dialogue mechanisms with potential bidders to help formulate specifications and evaluation criteria.

The authors would like to thank Teresa Rodriguez de las Heras Ballell and Taras Boichuk for their contribution to this article.

Few operational details are known about using eProcurement to select private parties in practice.

Given the large scale of most infrastructure projects, it is common for multiple operators organised in consortia to take part in concession procurement processes. Selection criteria, review and contract award rules should be adapted accordingly.

Several studies identify similarities in standard public procurement practices, but also important differences. In essence, a selection process of the private party in concessions/PPPs relies on similar legal instruments: qualification requirements (legal qualification, financial-economic capacity criteria, technical capacity or experience) and evaluation criteria (price only or price and quality) as standard public procurement contracts.

Multi-criteria evaluation is strongly recommended, as the characteristics of concession projects – developing, maintaining or operating public infrastructure or a facility and providing public services – require various criteria for a proper evaluation and comparison of proposals. Price is not the primary evaluation criterion, insofar as environmental sustainability, technical soundness, continuity requirements or social and economic development potential can be crucial policy goals in the procurement process. International standards as provided for by UNCITRAL instruments on public procurement differentiate evaluation criteria for the selection under PPP/concession projects from standard state budget-funded procurement.

Model Provision 19 of the UNCITRAL Model Legislative Provisions on PPP classifies evaluation criteria in those related to the technical elements of the proposals and those related to the financial and commercial ones. For the evaluation of the technical elements of the proposals, the following criteria shall at least be included: (a) technical soundness, (b) compliance with environmental standards, (c) operational feasibility and (d) quality of services and continuity-ensuring measures. For the evaluation of financial and commercial elements, relevant criteria should be considered, such as the value of the proposed tolls, unit prices and other charges or of the proposed direct payment by the contracting authority; the cost of the procured works; any financial support; proposed financial arrangements; social and economic development potential and even the extent of acceptance of the negotiable contractual terms recommended by the contracting authority in the request for proposals.

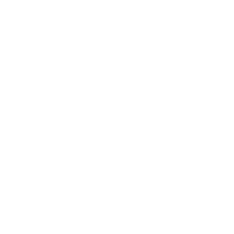

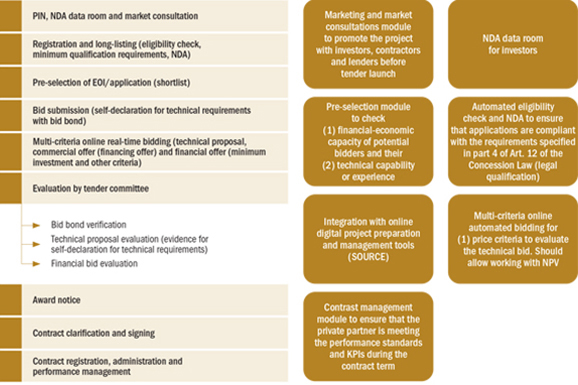

Also, user-pays PPP/concession projects require different procurement methods than government-pays PPP/concession projects. In the case of user-pays PPP/concession projects, the procurement process gives more weight to the qualification and selection of interested participants (Figure 1 below shows key features of the tender for user-pays concessions) and open tendering with pre-qualification or selective tendering/restricted tender with pre-selection are recommended. For government-pays PPP/concession projects, procurement focuses more on bid evaluation criteria, to facilitate better value for money and price-quality ratio of bids (Figure 2 shows key features of the tendering process for government-pays PPPs). As a result, open tendering with pre-qualification is more frequently used.

EOI: expression of interest

KPI: key performance indicator

NDA: non-disclosure agreement

NPV: net present value

PIN: prior information notice

Source: EBRD

NDA: non-disclosure agreement

PIN: prior information notice

Source: EBRD

In addition to the fairly standard public procurement policy considerations listed above, a procurement process for PPP/concession projects emphasises (a) defining qualification requirements and evaluation criteria in extensive communication with the market, (b) testing, marketing and communicating the project to the market well before the project launch and (c) allowing only qualified participants of the selection process invited to submit a bid to access certain financially sensitive project information.

These are instruments known and described in international legal instruments for public procurement, but not widely used for typical public procurement contracts. However, another feature of PPP/concession projects – final negotiation of the technical, legal and financial aspects of the bid and so-called financial closure of the deal – is heavily restricted or expressly forbidden under public procurement rules for standard state-funded procurement.

Given the large scale of most infrastructure projects, it is common for multiple operators organised in consortia to take part in concession procurement processes.

Why eProcurement?

eProcurement systems/platforms are designed to perform functions of the public procurement process with the assistance of digital technologies. eProcurement solutions vary from simple information-providing electronic websites to last-generation digital platforms supporting sophisticated procurement processes and using automation, robotics, artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies. Simple eProcurement systems supplement the manual public procurement process with online communication or online workflows for selected stages or tasks of process stakeholders to reduce some transaction costs without substantially altering the procedure. The latest generation of digital eProcurement tools represents a reshaping of the national procurement system and its transition to the digital economy. Digital eProcurement systems are designed, deployed and implemented as an end-to-end electronic process entrusted with the performance of all steps of the procurement process online.

On the global level, eProcurement is promoted by the regulatory standards of the 2011 UNCITRAL Model Law on Public Procurement and the 2012 text of the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Government Procurement, while the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recommended eProcurement to its members in 2015. The European Union (EU) mandated a certain level of eProcurement for member states in the 2014 directives on public procurement and promotes these policies externally by incorporating eProcurement requirements in relevant EU bilateral trade and association agreements. Although global rules on eProcurement are incorporated in regulatory frameworks for public procurement, eProcurement tools are not advanced enough everywhere to support all types of procurement methods. The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated development and implementation of eProcurement tools imposing remote working, less printing and paperwork in general and generalisation of online signature of contracts.

eProcurement is also a result of growing demand for more transparency in public procurement, necessary to fight corruption. Concerns about corruption, arbitrariness in awarding public contracts and/or lack of professional procurement capacities among public-sector officials guide the policy decision on accelerating the digital transformation of public procurement. Digital eProcurement tools, automation in the evaluation process and accessibility of public procurement open data throughout the entire procurement process are effective corruption-mitigating tools.

eProcurement is also a result of growing demand for more transparency in public procurement, necessary to fight corruption.

eProcurement for PPPs, including concessions: Suitability, benefits and challenges

Despite some potential advantages of eProcurement for PPP/concession projects, namely in terms of lower transaction costs, process efficiency and fighting corruption, progress has been slow.

The use of electronic communication in the procurement process for PPP/concession projects does not cause any specific difficulty and can be delivered under very simple eProcurement solutions. The problem starts with pre-qualification and qualification, where more comprehensive and advanced eProcurement digital tools are required for PPP/concession projects. In practice, the use of eProcurement (including automatic selection of the private partner/concessionaire) has been very limited worldwide.

However, the recent rapid development of digital eProcurement tools incorporating emerging technologies has enabled eProcurement to reach PPP/concession projects. This is because modern digital eProcurement systems can deliver online sophisticated, multi-stage procurement processes and effectively support online pre-qualification and pre-selection as well as multi-criteria evaluation methodologies. Key features of the procurement process for user-pays and government-pays PPP/concession projects, as described in Figures 1 and 2, are becoming available as default offerings of last-generation digital eProcurement systems.

New-generation eProcurement tools enable multi-attribute qualification and selection as well as evaluation with multiple non-price values required by public infrastructure projects. The selection stage is based on an assessment of the performance of the competing providers against a predetermined list of evaluation criteria, on the basis of a predefined framework of the weight, relevance and priority of such criteria. Such a selection process in public procurement may greatly benefit from data-driven electronic decision-making. Digital technologies, particularly robotics and automation, accelerate the processing of large amounts of data and information provided by selection participants. Multi-attribute auctions and multi/bilateral negotiations are possible models for concessions/PPPs. New technology means multi-criteria auction engines perform well with complex projects and it can handle high numbers of bidders. At the same time, the synchronous multi-criteria online bidding characteristic for auction models is driving economic value (cost savings and profit gains) and makes it possible to include non-financial and social aspects in the evaluation methodologies.

Finally, EU policies on digitalisation of public procurement have a significant impact on the procurement of PPP/concession projects, especially for the procurement process of non-concession PPP projects. EU policy does not distinguish between non-concession PPPs and standard public procurement of works and services, and except for concessions as precisely defined in the 23/2014/EU Concession Directive, all types of work or service contracts are to be considered as public procurement as far as the procurement process and contract award are concerned. Non-concession PPPs in EU member states (and associated countries) are therefore subject to national public procurement laws and have to follow the digitisation trend of the public procurement markets as prescribed by the 2014 EU directives on public procurement. Also, some EU member states and candidate countries (Estonia, North Macedonia, Slovakia) decided to directly apply the standard public procurement rules to all PPP/concession projects.

A recipe for eProcurement for concessions/PPPs

eProcurement for PPP/concession projects explores, leverages and selectively applies the widespread, entrenched and market-tested solutions for electronic procurement in the platform economy: electronic marketplaces, electronic trading systems, aggregators and comparators, smart contracts, recommender systems, ranking, rating and scoring.

Specific international legal standards on communications, attribution of legal effects, authentication, transfer of rights, negotiations or liability are available in UNCITRAL MLEC, MLES, MLETR and CEC26 and guide most practical steps in the design and operation of eProcurement for PPP/concession projects.

In addition, in-force and ongoing regional proposals on digital service providers, hosting services, online platforms and specific rating or recommender systems enable the future of eProcurement systems for PPPs as well as concessions as sophisticated digital ecosystems fed by data, driven by algorithm and artificial intelligence solutions and that are adaptative, reliable, dynamic and properly monitored.

In essence, developments in policy and emerging technologies teach us that the complete digitisation of procurement process for the PPP/concession projects is possible and it can be facilitated.

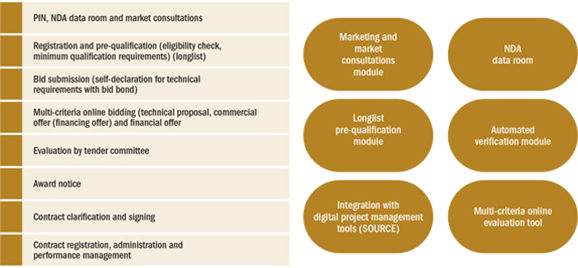

The Sustainable Infrastructure Foundation and its SOURCE platform promote one of the recently explored approaches. The SOURCE system is a multilateral platform for sustainable infrastructure led and funded by multilateral development banks. The SOURCE system supports the development of well-prepared projects to bridge the infrastructure gap and government digitalisation agendas. It provides a comprehensive map of all aspects of the preparation of sustainable infrastructure, for both standard procurement and PPPs, covering governance, technical, economic, legal, financial, environmental and social issues. It uses sector-specific templates covering the stages of the project cycle, spanning from project definition to operation and maintenance as well as allowing the definition of specific targets to fulfil the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement.

Why may the SOURCE system facilitate the use of eProcurement in PPP/concession projects? Because the platform provides tools for procurement process instruments that are typically non-standard for eProcurement platforms designed to support public procurement procedures, but essential for procurement of PPP/concession projects.

In particular, the SOURCE system provides data repositories and tools for defining qualification requirements and evaluation criteria in communication with the market, guides testing, marketing and communicating the project to the market before the project launch and, when required, provides virtual non-disclosure agreement data rooms to control access to sensitive project information. Therefore, a simple and far-reaching solution to introduce eProcurement to PPP/concession projects is to integrate a national-level eProcurement platform (or platforms) with the SOURCE system.

Source: EBRD

With this integration, as described in Figure 3, the SOURCE system serves non-standard parts of the procurement process for PPP/concession projects (project appraisal, non-disclosure agreement data room, market consultations, preparation of the tender), while a national eProcurement platform (or platforms) supports standard procurement processes of single-stage or two-stage tenders. Courtesy of cloud-based applications, the entire process is seamlessly integrated into a single window for all end-users/process stakeholders.

This is possible in practice when a national eProcurement system (or systems) belongs to the latest generation of digital eProcurement tools, is cloud-based and uses the same data standard as the SOURCE system – an open data standard for public procurement – Open Contracting Data Standard or OCDS.

The second condition for this rapid implementation of eProcurement in the procurement processes for PPP/concession projects is the availability of multi-attribute qualification, selection and evaluation among the functionalities of the national eProcurement platform(s). This too is facilitated by governance guidance embedded in the SOURCE system and it helps the project team access relevant standards for tender preparation and formulation of well-prepared qualification and evaluation methodologies. In the future, the SOURCE system may consider development of more eProcurement add-ins to provide not only support to project definition, tender preparation and contract management, but also a specialised standardised qualification and evaluation tools for the procurement process for concessions/PPP projects. This way, it enables integration with literally any national eProcurement platform.

The integration idea based on the interoperability data standard has great practical potential, and several governments in the EBRD region have expressed interest in collaborating with the Bank and the Sustainable Infrastructure Foundation to try the approach. The Legal Transition Programme, together with the EBRD Sustainable Infrastructure, is working on a conceptual design of eProcurement policies enabling a pilot of eProcurement for the concession/PPP procurement process by integrating a national-level eProcurement system with the SOURCE platform.

Enforcement of court decisions and the way forward to digital enforcement

Introduction

A healthy and attractive investment climate gives businesses trust that the judicial system will protect their legitimate interests and successfully enforce court decisions. The lack of effective enforcement mechanisms has a devastating effect on the investment climate and the rule of law, deterring local and foreign investment. One of the main problems in commercial disputes in the countries where the EBRD operates arises when a party tries to enforce a court’s decision.27 Previous EBRD research on judicial decisions found poor implementation of judicial rulings to be the biggest challenge, outranking even corruption. Another EBRD study of enforcement agents’ systems28 identified the following elements as most problematic in terms of enforcement and proposed measures to address them:

Most problematic dimensions of enforcement

- Searching for assets

- Sale of assets

- Speed of enforcement

- Supervision

- Seizure of assets

- Cost of enforcement

Measures to promote efficient enforcement

- Initial and ongoing training for enforcement agents

- Adequate pay and incentives

- Easy and efficient access to information in property registries and databases, including bank information

- Efficient sale and auction arrangements, including online procedures

- Robust financial deterrents for debtors who hinder enforcement

- Consistency of legislation on enforcement, property registries, privacy and banking

- Clear, consistent and publicly available statistical data on past and current cases

- Robust oversight of agents’ conduct

- Public debate of reports into allegations of corruption by enforcement officers29

In response, the EBRD, through its Legal Transition Programme (LTP), has focused its attention on reforms to improve the effectiveness of enforcement of judgments and the role of enforcement officers.

Despite the level of development of digital technologies around the world, the Covid-19 pandemic has revealed significant shortcomings in the activities of state bodies and the judiciary, including the enforcement system – namely, the absence or insufficient level of digitalisation of activities that would make it possible to work effectively when personal contact is impossible. This situation underscores the need to introduce digital technologies in the judicial system to guarantee access to justice and in enforcement procedures as an effective means of carrying out judgments.

It is worth noting that digitalisation is one of the strategic directions of the EBRD until 2025. The LTP will pay close attention to digital aspects to improve the enforcement systems in countries where the EBRD operates.

International enforcement standards and instruments and recent developments

The effective enforcement of court decisions is recognised as an integral part of the fundamental human right to a fair trial established by Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,30 Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights31 and Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights.32 The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has linked the enforcement of judgments to the requirements of the right to a fair trial under Article 6.33

Until recently, the enforcement of judgments was not the subject of extensive regulation in international law or standard setting among international organisations. However, interest is growing at the global and regional levels in undertaking work in the area of enforcement.

As the box below shows, there are now several good guiding standards and studies at the European and international levels.

- Council of Europe’s Recommendation (2003) 17 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on enforcement (CE Recommendation), September 20033435

- European Commission on the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) Guidelines for a better implementation of the existing Council of Europe’s recommendation on enforcement (CEPEJ Guidelines), December 200936

- CEPEJ Good practice guide on enforcement of judicial decisions, December 201537

- CEPEJ Specific Study on the Legal Professions: Enforcement Agents, 202138

- Global Code of Enforcement, May 2015,39 International Union of Judicial Officers (UIHJ)40

- Global Code of Digital Enforcement, November 2021, UIHJ41

Thanks to Patricia Zghibarta and Illia Chernohorenko, EBRD Consultants, for their contribution to this article, in particular on the Moldovan and Ukrainian experiences.

UNIDROIT’s standard-setting initiative on enforcement

The International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT)42 refined the undertaking of a project on “Principles of Effective Enforcement” in 2018.43 A working group was established in 2020 and this project is given high priority on the UNIDROIT Work Programme 2020-2022. The working group is tasked with developing a set of global standards and best practices to improve the domestic law framework for enforcement in the form of a guidance document.

Several global and regional organisations with expertise in this field – including the EBRD – were invited to participate as observers in the working group. The work is divided into three areas, one of which is the impact of technology on enforcement. Preparation of a first draft of the proposed instrument is expected to be concluded in 2022.44 The Bank contributed to this initiative by providing experience and lessons learned from implementing projects in the EBRD regions over the last decade.

Digitalisation of enforcement procedures

As already mentioned, past EBRD assessments have highlighted the importance of digital technologies in enforcement procedures. Emerging digitalisation – including in the justice sector – has had a major impact on the enforcement system in recent years. Until recently, however, there were no instruments to summarise best practice and define all the necessary aspects of digitalisation to enforce judgments effectively.

As noted above, the UIHJ Global Code of Digital Enforcement defines universal principles that apply to all facets of digital enforcement in civil matters. It encourages states to incorporate these principles in their national legislation when regulating the use of digital technologies in enforcement procedures. While the Code also refers to substantive matters, such as issues of enforcement of digital assets, the key aspects outlined below focus on the procedural aspects (electronic enforcement):

- Ensure that digital enforcement measures are proportional to the enforcement claim.

- Provide for the use of digital tools in enforcement agents’ activities, including the use of digital identity, in compliance with data protection and confidentiality rules.

- Enable the employment of secured online dispute resolution systems by enforcement agents, particularly online mediation, in the enforcement process.

- Ensure the necessary level of digital literacy of enforcement agents through training.

- Put in place infrastructure enabling enforcement agents to exchange information electronically regarding the debtor with other relevant institutions (for example, courts) and to access data from relevant electronic registers (for example, registers held by banks or asset registers).

- Ensure flexibility and allow the switch from digital to non-digital enforcement and vice versa, where necessary.

- Develop regulatory frameworks that permit the use of artificial intelligence with minimum risks, compliance with fundamental rights and ethical principles, and that allow enforcement agents to control and override the decisions made by artificial intelligence.

- Maintain a debtor’s access to offline (physical) contact with enforcement agents.

- Ensure reasonable, transparent and well-defined costs of digital enforcement, which in any event should not exceed the costs of non-digital enforcement.

As discussed above, UNIDROIT intends to develop a set of global standards and best practices for the enforcement of judgments, including digital aspects. These instruments will guide further reforms in the field of enforcement of judgments aimed at the introduction of e-enforcement procedures.

EBRD LTP support to improve enforcement of judgments

Since 2014, the LTP has implemented several enforcement reform projects – including in Mongolia, Tajikistan, Ukraine and the Kyrgyz Republic – that mainly targeted policy, legal and institutional development and capacity building. The focus since 2018 has also encompassed the digitisation of enforcement procedures. New projects were recently initiated in Moldova, Ukraine and Azerbaijan, and another is scheduled to launch in Mongolia in 2022. Some recent initiatives are highlighted below.

The Kyrgyz Republic

The Kyrgyz judicial system has suffered from a low level of enforcement of judgments for many years.45 One of the greatest challenges is the human resource capacity of the bailiff service, which lacks continuous training and has a workload that exceeds the bailiffs’ ability to handle it. There is a very low ratio of enforcement agents to residents in the country by regional standards. To help the Kyrgyz authorities enhance the capacity of Kyrgyz bailiffs to enforce judgments in commercial matters, the EBRD launched the Bailiff Service Capacity Building Project in Kyrgyz Republic in 2015. The project was implemented in three phases, from 2015-21.

Under the initial phase (2015-16), the Functional Analysis of the System of Court Enforcement in the Kyrgyz Republic was prepared in June 2016 to identify the areas for reform and offer recommendations. The new Law on Enforcement Process and the Status of Enforcement Agents (Enforcement Law or Law No. 15) was adopted on 29 January 2017.46 This law introduced useful reforms, though there is room for further improvements.

The Kyrgyz Republic has a state system of court enforcement. To enforce court decisions more efficiently, the government is considering introducing a mixed system of court enforcement that would include private bailiffs, as envisaged in the National Development Strategy of Kyrgyz Republic for 2018-2040.47

Under Phase 2 (2017-21), the project helped the Kyrgyz authorities implement the recommendations by providing legislative and institutional development advice, training of trainers and apprenticeship. As a result, the Court Department under the Supreme Court, responsible for enforcement of court decisions, adopted a comprehensive Strategy for the Institutional Development of the Court Enforcement Department, accompanied by the Action Plan for 2019-2021, in 2018.

In line with the Strategy, the project helped to develop legislative amendments to strengthen the enforcement function by creating a new State Court Enforcement Service under the Supreme Court (CDES) with a doubled staff48 and amending the Budget Code of the Kyrgyz Republic, with a focus on facilitating the financial sustainability and autonomy of the enforcement body and providing adequate incentives for bailiffs. The project further assisted by developing several drafts of secondary legislation concerning the functioning of the CDES and its staffing. The approval process of these documents was postponed because of drastic changes in the political landscape in the Kyrgyz Republic in 2020-21.

At the end of 2021, as a result of political changes and the Covid-19 pandemic, which led to a reduction in the state budget and state structures, the enforcement function was returned to the Court Department under the Supreme Court.49